Originally published November 15, 2022 12:29 PM EST on TIME

In mid-October, a pair of climate activists from the group “Just Stop Oil” garnered substantial international media attention when they threw tomato soup across Van Gogh’s Sunflowers in London’s National Gallery. “Are you more concerned about the protection of a painting or the protection of our planet and people?” they asked the shocked and visibly distraught crowd of onlookers.

Now I have devoted much of my time and effort over the past several decades to the cause of meaningful climate action. And as someone who also studies what makes for effective climate communication, I worried that events like this could harm the cause to which I (and so many) have devoted my life. I thought about the way the event would be framed by the media—the viral spread of a terrible photo of what certainly appears to be the defacement of an iconic and priceless piece of art, accompanied by damning headlines of wonton destruction.

My fears were realized. Characteristic of much of the media coverage, the New York Times ran an article headlined “Climate Protesters Throw Soup Over van Gogh’s ‘Sunflowers’” featuring the offending photo of the soup-splattered painting. Only if you made it to the end of the sixth paragraph did you learn that the painting was protected by a glass pane and not damaged.

The public outrage was palpable. The reliably progressive Dan Rather, a consistent advocate for urgent climate action, opined: “It’s destructive to protest the destruction of our planet by trying to destroy beautiful art.” Activists complained that Rather got it wrong—that the painting wasn’t actually destroyed. But the vast majority of the public, who like Rather were subject only to a photo and a headline, wouldn’t know that. They would only see a damning headline and photo. That could and should have been predicted by the architects of the protest. I weighed in on twitter: “If you’ve lost Dan, maybe rethink your strategy folks.”

Yet advocates of disruptive non-violent direct actions have argued that I and other critics were all wrong. We just didn’t get it! Our criticism was tantamount to attacking the youths themselves! Some compared the intervention to celebrated acts of civil protest by Gandhi and Martin Luther King (though conceding that a favorable view of the protest was contingent upon knowing that the painting wasn’t actually damaged).

But those actions at least made sense. Anti-war protests took place on college campuses among young people who were being drafted. Lunch counter sit-ins were protesting white-only policies. The painting protest, by contrast, seemed bizarre and pointless, with no obvious message about the climate crisis. Who was the target? Van Gogh? Oil paintings (get it)? From a communications standpoint, the protest seemed like an even bigger mess than the soup-splattered painting.

So was it? That’s what we attempted to assess using a recent survey of public opinion about this and other similar protests. We asked respondents three questions. First, does the public approve of using tactics like shutting down traffic or seemingly defacing rare art to raise attention to climate change? Second, do these tactics affect public beliefs surrounding human-driven climate change? And third, does the framing of these tactics (e.g. whether or not the art was actually damaged) influence that support?

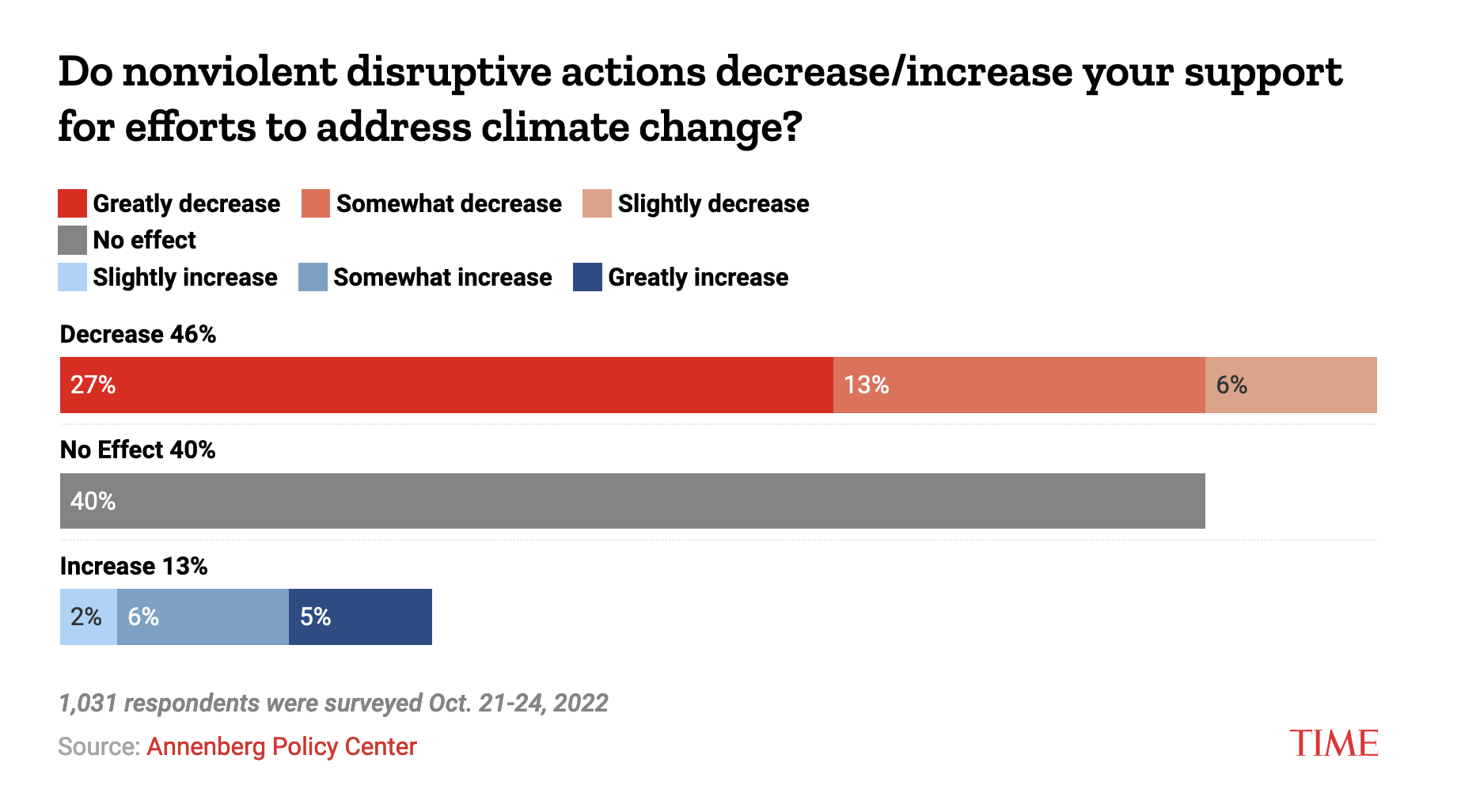

The survey confirmed what many had suspected. The public, overall, just doesn’t like this sort of stuff. A plurality of respondents (46%) reported that these tactics decrease their support for efforts to address climate change. A whopping 27%, in fact, said they greatly decrease their support. Only 13% reported increased support.

Some might suspect that the negative response is driven by older, out-of-touch folks reacting negative to the actions of the “young whipper-snappers.” It is true that younger respondents (18-29) were less likely to decrease support (39%) than the oldest (65+) respondents (53%). But all age groups showed decreased support.

Some observers have expressed incredulity over the notion that a non-violent protest could lead someone who cared about the future of the planet to no longer do so. It’s just not rational, they point out. And they’re right, it’s not rational. Because people aren’t always rational. Presumably these actions, at least for some individuals, create an affective rather than cerebral response, generating negative associations with climate activists. And that negative association translates to decreased support for their cause.

Given the political polarization that exists today on climate, we might not be surprised that Republicans reported the largest (69%) decrease in support. It is noteworthy however that even Democrats were more likely to report a decrease (27%) than an increase (21%). And independents, who might be critical in establishing majority support for aggressive climate policies expressed strong disapproval, with 43% reporting a decrease in support and only 11% reporting an increase.

The vitriol we experienced when we posted our findings on social media was perhaps not surprising given the anger toward critics at the time of the protests. But even academic proponents of these protests criticized and dismissed our findings, insisting the poll questioning was somehow loaded or misleading. My colleague Kathleen Hall Jamieson who helped design the survey has commented on the poll design: “The question is a neutral description of actions that occurred and were reported in news. A rationale for the actions is included in the question.”

The reader can judge for themselves. We first used a baseline question to assess respondents’ views of the climate crisis, asking whether or not they agreed with the statement: “Human use of fossil fuels creates effects that endanger public health.” More than 62% of the respondents answered in the affirmative, indicating that the group was predisposed, overall, to be concerned about fossil fuel burning and climate change.

They were then asked: “To raise awareness of the need to address climate change, some advocates have engaged in disruptive non-violent actions including shutting down morning commuter traffic and pretending to damage pieces of art. Do such actions decrease your support for efforts to address climate change, increase your support for efforts to address climate change or not affect your support one way or another?”

By describing protesters as “pretending” to damage art, we granted them the benefit of the doubt; we informed respondents, a priori, that the art wasn’t actually damaged. If anything, that should have primed an overly favorable response.

Critics of our study quickly brandished another recent (online) poll in the UK that purports a 66% level of support for nonviolent protests. They insisted it contradicts our findings. But that poll asked “Would you support taking non-violent direct action to protect the UK’s nature?” It didn’t even describe the disruptive acts in question, which means respondents weren’t confronted with the negative imagery of those acts. Furthermore, respondents were primed to give a positive response by being somehow promised that these protests would “protect the UK’s nature.” Were that environmental protection was that simple!

It takes substantial motivated reasoning to accept the findings of the UK survey and reject the findings of ours. And unfortunately, just as with climate change denial, there seems to be way too much motivated reasoning on the part of proponents when it comes to the topic of disruptive non-violent climate protests.

And what about the issue of whether or not the art was damaged. Did it matter to people? To investigate if that mattered to respondents, we split our poll sample. Half the sample was instead asked a slightly different version of the question, where “pretending to damage pieces of art” was changed to “damaging pieces of art.” The results were virtually identical, suggesting—somewhat surprisingly—that knowing that the art wasn’t actually damaged was not actually a mitigating factor with respect to public opinion. It didn’t matter. Presumably, it was the “thought” rather than the “act” that truly counted.

So, do our results suggest that there is no role for non-violent protest by climate advocates and activists? No. There are bad actors and villains in the climate space: Fossil fuel companies engaged in greenwashing campaigns, plutocrats who fund dark-money climate denial and delay campaigns, makers of gas-guzzling vehicles, the list goes on. A public opinion survey earlier this year by researchers at Yale and George Mason University finds that direct actions that target the bad actors (e.g. billionaires who fly fossil fuel-guzzling private jets) garner substantial support.

But actions that subject ordinary commuters to delays when they’re just trying to get to work in the morning, or subject art gallery visitors to the unpleasant, wanton apparent destruction of iconic artwork, are simply choosing the wrong targets. They are alienating potential allies in the climate battle. And protests that simply make no sense at all when reduced to a photo and a headline—which is what the vast majority of the public will see—are potential public relations disasters.

The youth protesters have their heart in the right place. But the organizations behind these protests need to do right by them by being smart about the design of any public interventions. That means, among other things, choosing sensible actions and appropriate targets. If we are to win the battle against polluters and their enablers, we will need public opinion on our side not theirs.

Note: The survey was designed in consultation with Kathleen Hall Jamieson, the founding director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC) and founder of factcheck.org. It was as part of a larger project examining public opinion on climate change and human health. The polling was conducted by SSRS, the same firm that conducted the late-breaking CNN polls that contradicted the “red wave” wrongly predicted by many other pollsters in the recent midterms. Analysis of the results was conducted by Ken Winneg, APPC’s Managing Director of Survey Research and APPC Research Analyst, Shawn Patterson Jr. (details can be found online).